I can’t stop thinking about it. It’s stuck in my head like Lola Young’s viral song "cause I’m too messy…”. If you know, you know.

I spoke about it briefly in December’s “How to Polish a Poem” workshop, and it’s been fermenting in the recesses of my brain ever since.

It’s the unexpected red-item theory.

If you hover and hang around the internet, you might have heard of it by now. Tiktokker Taylor Simon coined this term, and it’s the idea that in design, adding one singular red item that doesn’t belong to the space actually makes a space feel more put together, more cohesive. A pop of red in a bar stool, or a lampshade, or a pair of shoes carelessly tossed on the shoe rack supposedly adds an element of strangeness that humans are attracted to.

What I think we’re getting at is the idea of of lived-in ness, of imperfection. When everything goes perfectly, it…well doesn’t.

Of course, when I heard this, I thought of this concept in the context of poems. In the last year, I’ve taught dozens of craft workshops, and they’ve all focused on how to achieve a more cohesive poem, a tighter metaphor, and concise language. What I have lacked is the opposite: a search for an imperfect poem. A messy poem.

Sure, I want to write poems that are crafted well and that sing. I want to be intentional about my words because they deserve that. But what happens when we forget to leave room for an imperfect red surprise?

Growing up, my mother meticulously cleaned the house before anyone showed up. We all had to help out in a panicked marathon cleaning. There were never any “red items” left out for visitors to see.

Yet, some of my favourite memories as an adult have been popping by a friend's house and chatting for hours about the knick-knacks and projects on the go in their apartment.

Once, a friend of mine had an entire at-home wine operation in the middle of her living room. I’ve never been more fascinated in my life. Now, that’s a red item if I’ve ever heard of one.

So, how do we leave room for these unexpected out-of-place items in our poems? How do we write poems that invite readers to pop in? To chat about and be surprised by the red item? Allow me.

How to Write Lived-In Poems

Just as a red stool can transform a room, a single unexpected element can elevate a poem, making it feel more authentic and alive. Here’s how:

First, identify the level of clarity your poem currently has.

In a poem, generally speaking, we want all the threads of the poem to come together in a unified, clear fashion. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the poem has to make “sense” from a narrative sense, but the sounds, imagery, and tone should, for the most part, feel connected and cohesive.

Identify all the threads of your poem currently. Notice which ones are in conversation with each other. Does your image speak to the line breaks? Is your pacing in tandem with your tone? Do they clash? Do they match?

Once we’ve identified which parts are currently unified, we can manipulate them to include one (or a few) red items. Below are four.

Red item #1: Break one of your patterns.

There are so many ways to do this. In poetry, we can create patterns through sound repetition, sentence length, syntax structure, diction, imagery, and much more. (That’s overwhelming, I know.) So which ones to break? And how? Here are a few ways I would do it.

Firstly, instead of writing a poem with sentences of the same length, I would break the sentence length dramatically.

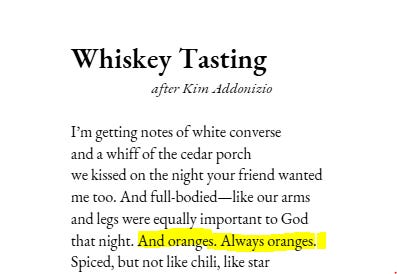

This is an excerpt from a poem I wrote after Kim Addonizio’s Wine Tasting. Notice how I break the two long sentences with two short ones. This adds surprise and also breaks the built-up tension in the first two sentences.

In the same way, instead of a poem with only cacophonic sounds, I would change the sounds where the poem's turn happens. When reading out loud, it should be obviously surprising where the shift happens.

You can do this with all the elements of poetry. Syntax, line breaks, tone, etc. Notice the patterns in your poem. Dare to break one (or two!).

Red Item #2: Create a Deliberate Misstep in Imagery

Use an image that feels slightly "off" or imperfect in its logic, yet evocative in its strangeness.

Instead of:

“The moon hung like a lantern above the dark city.”

Try:

“The moon hung like a ripe orange, sinking slowly into a bowl of smoke.”

Why it works:

The “orange” image disrupts the expected metaphor of the moon, drawing attention to the unique and peculiar quality of the comparison.

Paid subscribers have access to the rest of this lesson, a Red-Item Writing Challenge, and the in-depth video lesson. Join for $8/month!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Guelph Poet to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.